Biography of Gian Lorenzo Bernini

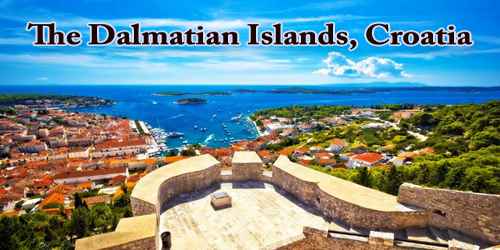

Gian Lorenzo Bernini – Italian sculptor and architect.

Name: Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Date of Birth: 7 December 1598

Place of Birth: Naples, Kingdom of Naples, in present-day Italy

Date of Death: 28 November 1680 (aged 81)

Place of Death: Rome, Papal States, in present-day Italy

Occupation: Sculpture, Painter, Architecture

Father: Pietro Bernini

Mother: Angelica Galante

Early Life

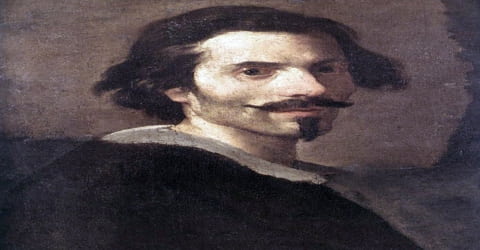

Seventeenth-century Italian architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini was born in Naples in 1598 to Angelica Galante and Mannerist sculptor Pietro Bernini, originally from Florence. His work is recognized throughout Italy. Bernini created the Baroque style of sculpture and developed it to such an extent that other artists are of only minor importance in a discussion of that style. As one scholar has commented, “What Shakespeare is to drama, Bernini may be to sculpture: the first pan-European sculptor whose name is instantaneously identifiable with a particular manner and vision, and whose influence was inordinately powerful….” In addition, he was a painter (mostly small canvases in oil) and a man of the theater: he wrote, directed and acted in plays (mostly Carnival satires), also he designed stage sets and theatrical machinery, as well as a wide variety of decorative art objects including lamps, tables, mirrors, and even coaches. As architect and city planner, he designed both secular buildings and churches and chapels, as well as massive works combining both architecture and sculpture, especially elaborate public fountains and funerary monuments and a whole series of temporary structures (in stucco and wood) for funerals and festivals.

Bernini possessed the ability to depict dramatic narratives with characters showing intense psychological states, but also to organize large-scale sculptural works that convey a magnificent grandeur. His skill in manipulating marble ensured that he would be considered a worthy successor of Michelangelo, far outshining other sculptors of his generation, including his rivals, François Duquesnoy, and Alessandro Algardi. His talent extended beyond the confines of sculpture to a consideration of the setting in which it would be situated; his ability to synthesize sculpture, painting, and architecture into a coherent conceptual and visual whole has been termed by the art historian Irving Lavin the “unity of the visual arts”. In addition, a deeply religious man (at least later in life), working in Counter-Reformation Rome, Bernini used to light both as an important theatrical and metaphorical device in his religious settings, often using hidden light sources that could intensify the focus of religious worship or enhance the dramatic moment of a sculptural narrative.

Bernini designed, sculpted, and built sculptures, tombs, altars, and chapels throughout Italy during his lifetime. He was also a leading figure in the emergence of Roman Baroque architecture along with his contemporaries, the architect Francesco Borromini and the painter and architect Pietro da Cortona. Early in their careers they had all worked at the same time at the Palazzo Barberini, initially under Carlo Maderno and, following his death, under Bernini. His design of the Piazza San Pietro in front of the Basilica is one of his most innovative and successful architectural designs. Within the basilica he is also responsible for the Baldacchino, the decoration of the four piers under the cupola, the Cathedra Petri or Chair of St. Peter in the apse, the chapel of the Blessed Sacrament in the right nave, and the decoration (floor, walls, and arches) of the new nave.

During his long career, Bernini received numerous important commissions, many of which were associated with the papacy. At an early age, he came to the attention of the papal nephew, Cardinal Scipione Borghese, and in 1621, at the age of only twenty-three, he was knighted by Pope Gregory XV. Following his accession to the papacy, Urban VIII is reported to have said, “It is a great fortune for you, O Cavaliere, to see Cardinal Maffeo Barberini made a pope, but our fortune is even greater to have Cavalier Bernini alive in our pontificate.” Although he did not fare so well during the reign of Innocent X, under Alexander VII, he once again regained pre-eminent artistic domination and continued to be held in high regard by Clement IX.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Italian pronunciation: ˈdʒan loˈrɛntso berˈniːni; also Gianlorenzo or Giovanni Lorenz), was born on December 7, 1598, in Naples, the sixth of thirteen children of Angelica Galante and Pietro Bernini. Bernini began his career under the direction of his father, Pietro Bernini, a Florentine sculptor. At a young age, his remarkable talent earned him the patronage of Pope Paul V. He would later say that ”Three things are needed for success in painting and sculpture: to see beauty when young and accustom oneself to it, to work hard, and to obtain good advice.”

Bernini was a deeply religious Catholic and created his first work at the age of eight. His father encouraged his skill, recognizing early the prodigy he would become. In fact, he was presaged, “the Michelangelo of his age,” according to Giovanni’s son and biographer Domenico Bernini. This lifelong dedication to practice would lead to Bernini’s development of his own style which would go on to greatly contribute to the Baroque movement.

In 1606 his father received a papal commission (to contribute a marble relief in the Cappella Paolina of Santa Maria Maggiore) and so moved from Naples to Rome, taking his entire family with him and continuing in earnest the training of his son Gian Lorenzo. Several extant works, dating from circa 1615-20, are by general scholarly consensus, collaborative efforts by both father and son: they include the Faun Teased by Putti (c. 1615, Metropolitan Museum, NYC), Boy with a Dragon (c. 1616-17, Getty Museum, Los Angeles), the Aldobrandini Four Seasons (c. 1620, private collection), and the recently discovered Bust of the Savior (1615-16, New York, private collection).

Bernini was strongly influenced by his close study of antique Greek and Roman marbles in the Vatican, and he also had an intimate knowledge of High Renaissance painting of the early 16th century. His study of Michelangelo is revealed in the St. Sebastian (c. 1617), carved for Maffeo Cardinal Barberini, who was later Pope Urban VIII and Bernini’s greatest patron. He established himself as an independent sculptor, with his first life-size sculptures commissioned by Scipione Cardinal Borghese, a member of the papal group.

The series included Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius Fleeing Troy, Pluto and Proserpina, Apollo and Daphne, and David (not to be confused with the well known Michelangelo sculpture). The series demonstrates Bernini’s development of his unique style that would be later termed as the Baroque Style. His sculptures enacted movement and true-to-life physical features of the mythological figures while remaining grand and exquisite.

Personal Life

In the 1630s Bernini had an affair with his assistant Matteo Bonarelli’s wife Costanza, during which he created a bust of her. This pioneered a new era in European sculpture as busts were usually formal portraits reserved for tombs, and had not been used for informal portraits since Ancient Rome. The bust expressed the desire and intimacy between Costanza and Bernini, which would eventually end in scandal.

She later had an affair with his younger brother, Luigi, who was Bernini’s right-hand man in his studio. When Gian Lorenzo found out about Costanza and his brother, in a fit of mad fury, he chased Luigi through the streets of Rome and into the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, threatening his life. To punish his unfaithful mistress, Bernini had a servant go to the house of Costanza, where the servant slashed her face several times with a razor. The servant was later jailed, and Costanza was jailed for adultery; Bernini himself was exonerated by the pope, even though he had committed a crime in ordering the face-slashing. This was a great scandal in Rome at the time, yet due to his position as the Pope’s friend, Bernini was not punished.

Instead, at age forty-one, Bernini was ordered to marry and thus pursued an arranged marriage with Caterina Tezio (age 22) in 1639. They later had eleven children. After his never-repeated fit of passion and bloody rage and his subsequent marriage, Bernini turned more sincerely to the practice of his faith, according to his early official biographers, whereas brother Luigi was to once again, in 1670, bring great grief and scandal to his family by his sodomitic rape of a young Bernini workshop assistant at the construction site of the ‘Constantine’ memorial in St. Peter’s Basilica.

Career and Works

Sometime after the arrival of the Bernini family in Rome, a word about the great talent of the boy Bernini got around and he soon caught the attention of Cardinal Scipione Borghese, nephew to the reigning pope, Paul V, who spoke of the boy genius to his uncle. Bernini was therefore presented before Pope Paul V, curious to see if the stories about Gian Lorenzo’s talent were true. The boy improvised a sketch of Saint Paul for the marveling pope, and this was the beginning of the pope’s attention on this young talent. Once he was brought to Rome, he rarely left its walls, except (much against his will) for a five-month stay in Paris in the service of King Louis XIV and brief trips to nearby towns (including Civitavecchia, Tivoli, and Castelgandolfo), mostly for work-related reasons. Rome was Bernini’s city: “‘You are made for Rome,’ said Pope Urban VIII to him, ‘and Rome for you’”. It was in this world of 17th-century Rome and religious power that Bernini created his greatest works.

“Apollo and Daphne” by Bernini (1622–25)

Under his patronage, Bernini carved his first important life-size sculptural groups. The series shows Bernini’s progression from the almost haphazard single view of Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius Fleeing Troy (1619) to strong frontality in Pluto and Proserpina (1621–22) and then to the hallucinatory vision of Apollo and Daphne (1622–24), which was intended to be viewed from one spot as if it was a relief.

Bernini is credited for starting the Baroque Style of art and architecture, characterized by enormous pieces that generate illusion through an ability to enact movement. His sculptures and architecture shifted away from the Mannerist style, which relied on exaggerated qualities and ornateness.

Bernini’s first mature sculpture was of Saint Lawrence, completed in 1617. It was described as an “act of pious devotion” to his patron saint and showcased the importance of religion and the theme of devotion, which continued throughout his artistic career. From 1618 to 1625, Bernini worked prolifically, creating masterpieces such as The Rape of Proserpina, David and Apollo, and Daphne. Alongside these large-scale sculptures Bernini also created portrait busts, capturing what is now described as a “speaking likeness,” or the capturing of a person in action or at the point of uttering words. He said that “the white marble has to assume the likeness of a person, it has to have color, spirit and life,” which made his busts differ from more traditional forms and paved the way for a new style.

Adapting the classical grandeur of Renaissance sculpture and the dynamic energy of the Mannerist period, Bernini forged a new, distinctly Baroque conception for religious and historical sculpture, powerfully imbued with dramatic realism, stirring emotion and dynamic, theatrical compositions. Bernini’s early sculpture groups and portraits manifest “a command of the human form in motion and a technical sophistication rivalled only by the greatest sculptors of classical antiquity.”

In 1629, Bernini became the chief architect of the Fabric di San Pietro, the institution responsible for maintaining St. Peter’s Basilica. In August of the same year, Bernini’s father died, but Bernini still produced, solidifying his period of dominance in Rome. His association with the court of Rome lasted for fifty years along with close ties to each Pope. According to art historian Daniele Pinton, this was significant because “the history of art affords no other examples with such characteristics, of such creative continuity, for such a long time, by the work of a single artist.”

Under the influence and patronage of pontificate Urban VIII, Bernini built his masterpiece, the baldachin at St. Peter’s Basilica between 1624 and 1633. The baldachin is a gilt-bronze structure featuring twisted columns and crowning volutes with four angels supporting an orb and cross. The structure is nearly four stories tall and is considered the first integrated piece of Baroque architecture and art. During this time, he executed a series of busts of Urban VIII, but none were as successful as his bust of Scipione Cardinal Borghese, which was revealed in 1632. The bust exhibits great movement with the cardinal in the act of speaking and moving.

Bernini worked closely with his brother Luigi and was naturally entrepreneurial, remaining the dominant sculptor and architect in the city. He often clashed with Francesco Borromini, another noted architect who often lost out on work to Bernini due to the Pope’s favoritism. Bernini’s workshop was organized like a factory; he rarely refused commissions and delegated work to his assistants, even collaborating once with Borromini on St. Peter’s Baldachin despite their rivalry.

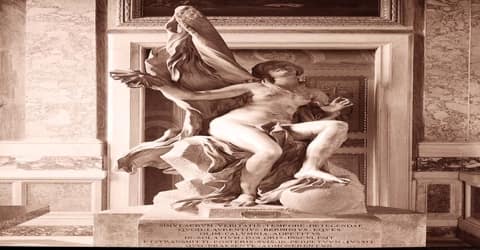

(Truth Unveiled by Time, Galleria Borghese, Rome)

Bernini next supervised the decoration of the four piers supporting the dome of St. Peter’s with colossal statues, though only one of the latter, St. Longinus, was designed by him. He also made a series of portrait busts of Urban VIII, but the first bust to achieve the quality of his earlier portraits is that of his great patron, Scipione Cardinal Borghese (1632). The cardinal is shown in the act of speaking and moving, and the action is caught at a moment that seems to reveal all the characteristic qualities of the subject. He was successful in organizing his studio and planning his work so that sculptures and ornamentations produced by a team actually seem to be all of a piece. Bernini’s work, then and always, was also shaped by his fervent Roman Catholicism.

Bernini also began work on the tomb for Urban VIII, completed only after Urban’s death in 1644, one in a long, distinguished series of tombs and funerary monuments for which Bernini is famous and a traditional genre upon which his influence left an enduring mark, often copied by subsequent artists. Indeed, Bernini’s final and most original tomb monument, the Tomb of Pope Alexander VII, in St. Peter’s Basilica, represents, according to Erwin Panofsky, the very pinnacle of European funerary art, whose creative inventiveness subsequent artists could not hope to surpass.

He would agree with the formulations of the Council of Trent (1545–63) that the purpose of religious art was to teach and inspire the faithful and to serve as propaganda for the Roman Catholic Church. Religious art should always be intelligible and realistic, and, above all, it should serve as an emotional stimulus to piety. The development of Bernini’s religious art was largely determined by his conscientious efforts to conform to those principles.

Beginning in the late 1630s, now known in Europe as one of the most accomplished portraitists in marble, Bernini also began to receive royal commissions from outside Rome, for subjects such as Cardinal Richelieu of France, Francesco I d’Este the powerful Duke of Modena, Charles I of England and his wife, Queen Henrietta Maria. The sculpture of Charles I was produced in Rome from a triple portrait (oil on canvas) executed by Van Dyck, that survives today in the British Royal Collection. The bust of Charles was lost in the Whitehall Palace fire of 1698 (though its design is known through contemporary copies and drawings) and that of Henrietta Maria was not undertaken due to the outbreak of the English Civil War.

Under Urban VIII Bernini began to produce new and different kinds of monuments tombs and fountains. The tomb of Urban VIII (1628–47) shows the pope seated with his arm raised in a commanding gesture, while below him are two white marble figures representing the Virtues. Bernini also designed a revolutionary series of small tomb memorials, of which the most impressive is that of Maria Raggi (1643). But his fountains are his most obvious contribution to the city of Rome. The Triton Fountain in the Piazza Barberini (1642–43) is a dramatic transformation of a Roman architectonic fountain the superposed basins of the traditional geometric piazza fountain appearing to have come alive. Four dolphins raise a huge shell supporting the sea god, who blows water upward out of a conch.

In 1637 Bernini began to erect campaniles, or bell towers, over the facade of St. Peter’s. But, in 1646, when their weight began to crack the building, they were pulled down, and Bernini was temporarily disgraced.

Nonetheless, Bernini’s opponents in Rome succeeded in seriously damaging the reputation of Urban’s artist and in persuading the pope to order (in February 1646) the complete demolition of both towers, to Bernini’s great humiliation and indeed financial detriment. After this, one of the rare failures of his career, Bernini retreated into himself: according to his son, Domenico. his subsequent unfinished statue of 1647, Truth Unveiled by Time, was intended to be his self-consoling commentary on this affair, expressing his faith that eventually Time would reveal the actual Truth behind the story and exonerate him fully, as indeed did occur.

His most spectacular public monuments date from the mid-1640s to the 1660s. The Fountain of the Four Rivers in Rome’s Piazza Navona (1648–51) supports an ancient Egyptian obelisk over a hollowed-out rock, surmounted by four marble figures symbolizing four major rivers of the world. This fountain is one of his most spectacular works.

During Pope Alexander VII’s pontificate (1655-67), Bernini attempted to transform Rome through a costly urban planning project. He managed to recreate the “glory of Rome” that had begun in the 15th century, and he focused on architecture including the piazza leading to St Peter’s.

Bernini’s creations during this period include the piazza leading to St Peter’s. In a previously broad, unstructured space, he created two massive semi-circular colonnades, each row of which was formed of four white columns. This resulted in an oval shape that formed an inclusive arena within which any gathering of citizens, pilgrims and visitors could witness the appearance of the pope either as he appeared on the loggia on the facade of St Peter’s or on balconies on the neighboring Vatican palaces. Often likened to two arms reaching out from the church to embrace the waiting crowd, Bernini’s creation extended the symbolic greatness of the Vatican area, creating an “exhilarating expanse” that was, architecturally, an “unequivocal success”.

The greatest single example of Bernini’s mature art is the Cornaro Chapel in Santa Maria Della Vittoria, in Rome, which completes the evolution begun early in his career. The chapel, commissioned by Federigo Cardinal Cornaro, is in a shallow transept in the small church. Its focal point is his sculpture of The Ecstasy of St. Teresa (1645–52), a depiction of a mystical experience of the great Spanish Carmelite reformer Teresa of Ávila. In representing Teresa’s vision, during which an angel pierced her heart with a fiery arrow of divine love, Bernini followed Teresa’s own description of the event. The sculptured group, showing the transported saint swooning in the void, covered by cascading drapery, is revealed in celestial light within a niche over the altar, where the architectural and decorative elements are richly joined and articulated. At left and right, in spaces resembling opera boxes, numerous members of the Cornaro family are found in spirited postures of conversation, reading, or prayer.

Ecstasy of St. Teresa Gianlorenzo Bernini (1645-1652)

The figures of St. Teresa and the angel are sculptured in white marble, but the viewer cannot tell whether they are in the round or merely in high relief. The natural daylight that falls on the figures from a hidden source above and behind them is part of the group, as are the gilt rays behind. The Ecstasy of St. Teresa is not sculpture in the conventional sense. Instead, it is a framed pictorial scene made up of sculpture, painting, and light that also includes the worshiper in a religious drama.

Bernini worked for a stint in Paris in 1665 and this was the only substantial amount of time he was away from Rome since arriving from Naples. He became a popular figure while in France, even being recognized as he walked Parisian streets. King Louis XIV had invited Bernini and other Italian architects to work on the Louvre Palace but Bernini’s designs were rejected. He was open about his dislike for French culture and art, making it difficult to gain further commissions in Paris and Bernini’s only artwork that remains from this time is a bust of King Louis XIV. After returning to Rome Bernini created an equestrian statue of Louis XIV but when it was delivered to Paris, Louis XIV was unhappy with it and had the head replaced.

Bernini presented finished designs for the east front (i.e., the all-important principal facade of the entire palace) of the Louvre, which was ultimately rejected, albeit formally not until 1667, well after his departure from Paris (indeed, the already constructed foundations for Bernini’s Louvre addition were inaugurated in October 1665 in an elaborate ceremony, with both Bernini and King Louis in attendance). It is often stated in the scholarship on Bernini that his Louvre designs were turned down because Louis and his financial advisor Jean-Baptiste Colbert considered them too Italianate or too Baroque in style. In fact, as Franco Mormando points out, “aesthetics are never mentioned in any of the . . . surviving memos” by Colbert or any of the artistic advisors at the French court. The explicit reasons for the rejections were utilitarian, namely, on the level of physical security and comfort (e.g., location of the latrines).

Of the churches he designed after completing the Cornaro Chapel, the most impressive is that of Sant’Andrea al Quirinale (1658–70) in Rome, with its dramatic high altar, soaring dome, and unconventionally sited oval plan. But Bernini’s greatest architectural achievement is the colonnade enclosing the piazza before St. Peter’s Basilica. The chief function of the large space was to hold the crowd that gathered for the papal benediction on Easter and other special occasions.

Bernini did not build many churches from scratch; rather, his efforts were concentrated on pre-existing structures, such as the restored church of Santa Bibbiana and in particular St. Peter’s. He fulfilled three commissions for new churches in Rome and nearby small towns. Best known is the small but richly ornamented oval church of Sant’Andrea al Quirinale, done (beginning in 1658) for the Jesuit novitiate, representing one of the rare works of his hand with which Bernini’s son, Domenico, reports that his father was truly and very pleased. Bernini also designed churches in Castelgandolfo (San Tommaso da Villanova, 1658–61) and Ariccia (Santa Maria Assunta, 1662–64).

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Self-Portrait, c. 1665

Back in Rome Bernini continued to work for Pope Alexander VII then Pope Clement IX, carrying out improvements for cathedrals and churches in the city. He also created Pope Clement IX’s tomb monument and a statue of the successive pope Clement X. Bernini’s final work was Salvator Mundi, finished in 1679. It is a marble sculpture of Christ, which he described as his “darling” created out of devotion.

Bernini’s greatest late work is the simple Altieri Chapel in San Francesco a Ripa (c. 1674) in Rome. The relatively deep space above the altar reveals a statue representing the death of the Blessed Ludovica Albertoni. Bernini consciously separated architecture, sculpture, and painting for different roles, reversing the process that culminated in the Cornaro Chapel. In that sense, the Altieri Chapel is more traditional, a variation on his church interiors of the preceding years. Instead of filling the arched opening, the sculpted figure of Ludovica lies at the bottom of a large volume of space and is illuminated by a heavenly light that plays on the drapery gathered over her recumbent figure. Her hands weakly clutching her breast make explicit her painful death.

Awards and Honor

In 1621, at the age of only twenty-three, Gian Lorenzo Bernini was knighted by Pope Gregory XV.

Death and Legacy

Gian Lorenzo Bernini died in Rome on 28 November 1680 and was buried, with little public fanfare, in the simple, unadorned Bernini family vault, along with his parents, in the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore.

When Bernini died he was widely considered not only Europe’s greatest artist but also one of its greatest men. He was the last of Italy’s remarkable series of universal geniuses, and the Baroque style he helped create was the last Italian style to become an international standard. His death marked the end of Italy’s artistic hegemony in Europe. The style he evolved was carried on for two more generations in various parts of Europe by the architects Mattia de’ Rossi and Carlo Fontana in Rome, J.B. Fischer von Erlach in Austria, and the brothers Cosmas and Egid Quirin Asam in Bavaria, among others.

Though an elaborate funerary monument had once been planned (documented by a single extant sketch of circa 1670), it was never built and Bernini remained with no permanent public acknowledgement of his life and career in Rome until 1898 when a simple plaque and small bust was affixed to the face of his home on the Via Della Mercede, proclaiming “Here lived and died Gianlorenzo Bernini, a sovereign of art, before whom reverently bowed popes, princes, and a multitude of peoples.”

Bernini had a major impact on the city of Rome, shaping its architecture and leaving a mark that few artists have since. Bernini is part of a succession of great Italian sculptors placed alongside Donatello, Michelangelo, and Canova. By the end of his life, there was a reaction against the extravagance of his work. Scholars like Johann Winckelmann believed art should appeal to the mind whereas Bernini’s art appealed excessively to the senses. In fact, “Baroque” was initially deemed a derogatory term in regards to the theatrical nature of Bernini’s and other artists’ work. However, by the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries, art historians began re-evaluating Bernini’s work, writing about the Baroque movement positively, and in the last few decades, there have been multiple exhibitions of Bernini’s work, placing him as the indisputable father of Baroque sculpture.

Information Source: